The Cause of Freedom, 1870s-1899

The cause of freedom...is the cause of humankind, the birthright of humanity.

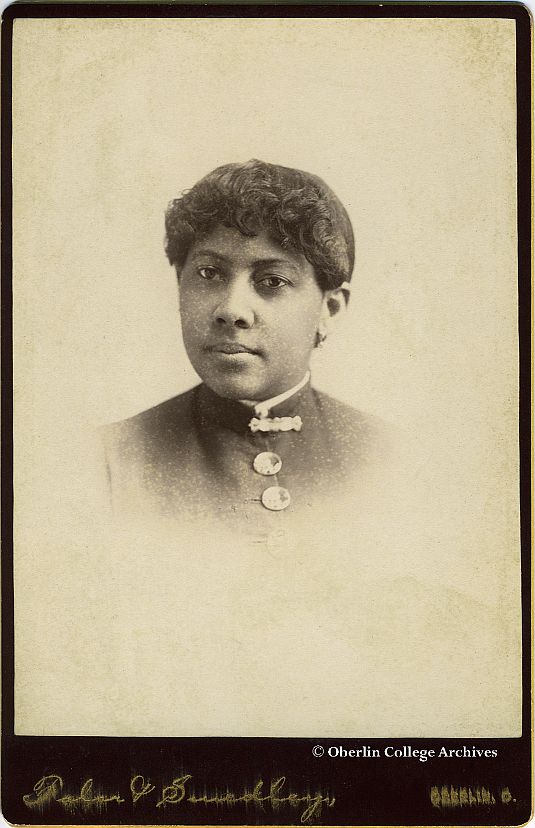

-- Anna Julia Cooper, Oberlin College Class of 1884

Introduction

The end of the Civil War and the debate over the 15th Amendment rekindled the women’s rights movement. Women across the country and around the world organized protests, printing campaigns, and political groups dedicated to granting women full agency in a free society.A splintered organization, harsh criticism, and vehement opposition crippled the women’s suffrage movement when the issue returned to the national spotlight in the 1870s. In addition to the ideological split of 1869, the women’s suffrage movement fractured along racial lines as well. African American women were often excluded from women’s suffrage events or local chapters of organizations due to their race. Activists such as Mary Church Terrell (OC 1884), Anna Julia Cooper (OC 1884), and Mary Burnett Talbert (OC 1886) [pictured below] objected strongly to this segregation, even while working tirelessly in their chosen fields and in national campaigns.

While the women’s suffrage campaign fragmented, an anti-suffrage campaign solidified. Anti-suffragists accused women who wanted the vote of being unfeminine, immoral, and selfish. Even at Oberlin College, which had been so eager to adopt coeducation, anti-suffrage sentiment prevailed. James Fairchild, president of Oberlin College, considered the idea of women’s suffrage such an outrage that he preached a sermon against it on campus. In 1870, the sermon, which eviscerated the women’s suffrage movement, was published in the form of a booklet entitled “Women’s Right to the Ballot.” His disapproval was echoed by Dascomb, who organized over a hundred women in and around Oberlin to express their condemnation of demands for female enfranchisement.

Much as the suffragists had done in the 1850s, the anti-suffragists embarked on a print campaign in the 1870s. Objections to women’s suffrage were printed in quantity, a trend which continued well into the 20th century.

In response to these attacks, suffragists endeavored to remind society that enfranchisement was key to freedom. Without the vote, they claimed the women of society were denied their freedom. African American women, in particular, were vocal on the point of enfranchisement being necessary for true freedom, and Cooper attempted to bridge the racial gap by claiming that the cause of freedom is “the birthright of humanity.”

Printed material flooded the market from both sides of the issue. Texts would often be published as a response to other publications, specifically citing them and refuting their arguments. Such reading matter and the arguments contained therein found an audience in the new group of women which was emerging: w omen in business.

More women were working outside the home and were holding more prominent positions than they had before. Katharine Wright Haskell (OC 1898), for instance, was the face of the Wright Brothers' business, meeting with investors, politicians, and even royalty on her brothers' behalf. Haskell, and other women like her, proved that women could be productive members of society and engage effectively in roles not traditionally designated for women. She adamantly argued that women in the workplace needed the right to vote in order to be truly equal to the men with whom they worked side-by-side.

As a counterpoint to the anti-suffragists' claims of immorality, the women’s suffrage campaign became aligned with a moral reform movement in the 1870s: the temperance movement. While some moral reformers worked to block women’s suffrage, the temperance movement fully embraced the women’s suffrage movement, realizing the temperance reform would be carried by the female population. Frances Willard, who had been raised in Oberlin and became the head of the nationwide Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), openly promoted the efforts of suffrage activists. Even members of local chapters, such as Frances Ensign Fuller (OC 1884), the secretary of the Ohio chapter of the WCTU, supported suffrage as a part of their regular program.

In 1890, after years of division and often conflicting campaigns, the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association reunited as a single body and became the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The new conglomerate organization provided a much more cohesive message and campaign strategy than before, and women’s suffrage began to make headway. African American women, however, were still largely excluded from these operations, and worked for suffrage through other avenues. The issue was now primed for a truly national debate.

This page has paths:

This page references:

- Woman's Right to the Ballot

- Portrait of Katharine Wright Haskell

- Address of Frances E. Willard, President of the Woman's National Council of the United States, Founded in 1888, at its First Triennial Meeting, Albaugh's Opera House, Washington, D.C., February 22-25, 1891

- Portrait of Frances Ensign Fuller